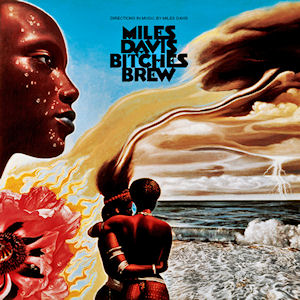

Miles Davis always seemed to have one foot in the present and one foot pointing to the future, and at the beginning of 1968, it was clear in which direction he was heading. The year began with the release of Nefertiti in March 1968. Nefertiti was recorded in June and July of 1967, and would end up being his last fully acoustic album, as well as the last record that the Quintet would play as they were constituted. All of the songs were composed by Herbie Hancock and Wayne Shorter, with the exception of Tony Williams' "Hand Jive". The album is outstanding, and the opening track, "Nefertiti", is a perfect demonstration for Williams' brilliant drumming. In fact, the whole band played up to their exceptional level, even though their time was coming to an end. Davis had become increasingly enamored with the rock-and-roll scene of the time, and was particularly fascinated with guitar virtuoso Jimi Hendrix. Accordingly, his next album Filles de Kilimanjaro from 1968, would be his first excursion in electronic experimentation. Miles would also add two new musicians: pianist Chick Corea and British bassist Dave Holland. Both Hancock and Corea would play the electric Rhodes piano in favor of an acoustic one, and Holland and Carter would play electric bass guitars. This definitely gives the album a much different feel than anything Davis had previously done, and the rock elements can be heard throughout. Ralph Gleason was right when he said there is a mystic quality to the record, and this was probably because no one had ever heard anything like it before. It was the first shot fired in the jazz fusion genre, and fittingly, it was Miles Davis holding the smoking gun. Both Filles de Kilimanjaro and its follow-up, In a Silent Way were warm-ups for the revolutionary double album, Bitches Brew. Recorded just weeks after the Apollo 11 moon landing, Bitches Brew took things a giant leap forward for the jazz-rock style. All of the members of the classic Quintet were gone except for Wayne Shorter, and close to a dozen musicians contributed to the album, including guitarist John McLaughlin. Like Kind of Blue, recorded a decade before, Bitches Brew has had a tremendous influence on other musicians. Thom Yorke of Radiohead said: "It was building something up and watching it fall apart, that's the beauty of it. It was at the core of what we were trying to do with OK Computer." Jazz music was changing along with the times, and jazz musicians replaced their suits and ties with bell-bottoms and bandanas. Probably no one could have imagined at the beginning of the decade that jazz would sound like this barely ten years later. While the album received mostly positive reviews, it also alienated many Davis fans and purists, who didn't consider it jazz at all. There were even some who charged Miles with selling out to gain more sales, especially among the younger black audience.