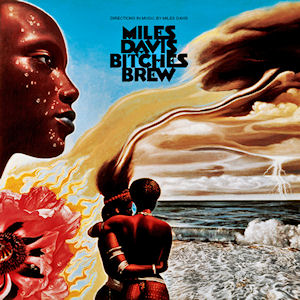

Bitches Brew, however polarizing, produced the desired effect, and Miles Davis gained many new followers with his synthesis of rock, funk, and jazz. Along with his music, Miles' whole appearance changed, as he adopted the persona of a rock star. Much of this was influenced by his new wife, Betty Mabry. She was a funk singer nearly 20 years his junior, and was hip to the latest fashions of the day. They were only married for about a year, but she had a major effect on Miles' style throughout this period. Although it was in keeping with the era, Miles seemed too old for the part, and he caught considerable flack for his sudden transformation. Nevertheless, jazz-rock was now dominating the jazz world, and it would be difficult to find anyone still playing acoustic hard bop anymore. Two exceptions would be Art Blakey, and Miles' former piano player Bill Evans. Herbie Hancock and Tony Williams followed Davis's lead, forming their own fusion bands shortly after leaving him, with Hancock using the electric piano almost exclusively during the '70s. Davis would continue to expand on the music of Bitches Brew during the '70s, and would also continue to draft many up-and-coming young musicians into his bands. Not many would stay too long, as Miles was restless and forward thinking, always eager for transfusions of new blood to fill his rhythmic veins. In 1970, Davis recorded Miles Davis at Fillmore, taken from four live shows he played at the Fillmore East in New York City. One of his most lauded albums from this period was A Tribute to Jack Johnson, recorded in February and June of 1971. Another talented group backed him on this record: guitarist John McLaughlin, drummer Billy Cobham, bassist Michael Henderson, and saxophonist Steve Grossman. Herbie Hancock rejoined his former boss for the album as well. A series of health issues would drive Miles into a dark, drug-riddled seclusion that would reach its nadir in the late '70s. Returning in the early '80s, he was much less discriminatory in who he played with, even to the point of recording with pop starlet Cyndi Lauper and new wave group Scritti Politti. Even though Miles might have lost part of his musical ability, he always seemed to have the brightest talent playing around him. Miles Davis died on September 29, 1991 at the age of 65. At the time of his passing, he had been recording material with hip hop producer Easy Mo Bee, in an album that would be released as Doo-Bop. Davis was also an admirer of the Beastie Boy's album Paul's Boutique, and many hip hop artists have sampled his music, including Gang Starr and Mobb Deep. Up until the very end, Miles was trying to stay relevant by keeping up with the latest musical trends. I don't think there will ever be another musician who will match his accomplishments, or the quality and scope of his music.